I chose two very different collections for this writing, the extensive online catalog for the Library of Virginia and the smaller online catalog for the Museum of the Rockies, part of Montana State University. I wanted to see how different institutions with different resources at their disposal handled the disparities and contradictions of describing a visual object via text, and how this affected the ease with which I could navigate the catalog. The images in the Library of Virginia catalog are rights-protected and would have cost money to reproduce. The Museum of the Rockies has no such restriction. Therefore, I have limited the visual offerings from the Library of Virginia to screen shots of the catalog records.

The Library of Virginia’s online catalog consists of several thousand photographs, among other types of media, digital and not. The photographs are for the most part described thoroughly, cross-indexed accurately and consistently, and equal attention has been paid to collection-level and item-level description.

Below is a screen shot of a collection-level entry, for the Lee F. Rodgers Photograph Collection.

The information displayed here is fairly minimal, although not inappropriately so. Thumbnails would make this content more scannable and the searching experience more pleasant. The user clicks on the check box to select an item, clicks on “View Selected”, and is brought to the item-level record, where the image is available via clicking on the URL. The actual image is three clicks away from the collection-level record, and it was not immediately clear to me how to view it, another reason why thumbnails would be useful.

This catalog encompasses many collections. Some of the more recent collections do feature thumbnails as an aid to searching.

It is worth noting that when I returned to the site, I had some difficulty locating the particular records I had been referencing before. It was frustrating to realize the level of detail that went into describing these items and also be struggling simply to return to where I was before. In that sense, this collection is over-described. The above screen shot is taken from a keyword search for “Lee F. Rodgers Photograph Collection” from the Library of Virginia’s home page, which is not the original route I used to find this collection. It is also noteworthy that the results here are almost, but not quite, identical to the search results obtained from clicking on “Lee F. Rodgers Photograph Collection” in the added title field of an item in this collection. It is unclear if this is simply a difference in display order or a difference in metadata.

An individual record in the Lee F. Rodgers Photograph Collection is shown below. The record is shown via two screen shots due to a discrepancy in monitor sizes.

This individual record clearly shows the creation of many access points, as exemplified by title, which can be found using either “Pvt.” or “Private”. The added titles, “Lee F. Rodgers Photograph Collection” and “Portsmouth Public Library Photograph Collection”, are searchable for collection-level records and serve to locate this collection within the larger Portsmouth Public Library collection. I found this photograph while searching for the Library’s collection of photographs from the Army Signal Corps; this is not in that collection (nor did I find the collection) but was picked up by the words “Signal” and “Corps” in the general note, where the full title, derived from the caption, is listed. I found the collection by finding the photograph, which means the description is sound.

The use of access points such as “Georjen Photographic Artists” and “Anniston (Ala.)” is typical of records in this collection, showing a level of detail and consistency that would be valuable to a very specific class of searcher.

I personally find the General Note field very pleasing in this case. The lengthy title, which according to the record is taken from the caption, puts the photograph in context and gives Private June E. Dove a life, a town, a school, a mother. It takes this textual information to give the photograph that dimensionality. However, that is a subjective response on my part, and I can also question the usefulness of including all of this information, beyond completeness for its own sake. How useful is this information, really, to someone searching this catalog?

Despite the thorough nature of item-level description in this catalog, it is not perfect. Below is another record, this one located by a search for “Virginia Beach.”

Here the subject list is comprehensive with one exception. Above the street in the photograph runs a banner for a blood drive, with the words “Protect Yourself Be A Blood Donor.” This is a major element of the photograph and it was one of the first things I noted, yet nowhere in the record is there any mention of “blood donor” or “blood drive.” There is a mention of banners under “Genre/Form”, which does not make sense. The photograph is not a banner. Other than that, the long list of subjects conveys a fairly accurate sense of a photograph in which a lot of activity is occurring.

On the subject of thumbnails, some of the newer collections in the online catalog do feature thumbnails as a searching aid. I find them invaluable. Photographs are a visual medium and this only makes sense given the inherently problematic nature of creating text descriptions for a visual item such as a photograph.

The Museum of the Rockies Photo Archive Online, of Montana State University, is a very different, much more simply described collection, and much more inherently navigable. It should also be noted that this catalog represents an ongoing digitization project at the university.

The records in this collection contain less metadata and less indexing. The collection-level record for the Ron V. Nixon Collection is searchable with a series of links rather than search fields. In that sense, a controlled vocabulary of access points is provided, ready-made, for the user. A search by subject yields another list of pre-defined subject terms, shown below. This list, presented in the left sidebar, remains present as the user navigates the images.

This catalog does not have the advanced search capabilities of the Library of Virginia catalog, but it does provide thumbnail images, each with an option to click to enlarge. These make the catalog easy to scan, particularly for someone who is browsing rather than searching.

Only the major subjects are listed in this record, a more simplified approach than that of the Library of Virginia. There is no mention in subjects of the Missouri River, over which this bridge is built and which is noted in the caption. The river is not included as an access point. However, the audience for this collection is probably going to be a casual searcher or a railroad fan, unlikely to be searching for images of the Missouri River specifically. Presumably, Montana State University does not have unlimited resources to dedicate to this project, and tailoring access points in this case shows a familiarity with the collection’s audience and a wise use of the resources they have.

The record number is listed not in the photograph metadata but in the heading for the image.

There is no link attached to the photographer’s name. The collection can be searched by photographer, but there are missing and incomplete records there. The listing of photographers is inconsistently organized, as shown below.

Apparently, the photographers are listed alphabetically by first name if it is known, last name if not. C C Wamsley appears in the C’s but not in the W’s. There are also two women photographers listed under Mrs. (presumably husband’s name), and they are located in the M’s under Mrs., rather than by name. Other women photographers are listed in the same manner as the male photographers, by first name. Non-individual photographers, such as Eng Dept, are listed under the first letter of the first word. This makes searching for a particular photographer’s work in the collection far more difficult. Some of it may be the result of gaps in knowledge, but a consistent by-last-name scheme would clear much of that up.

Again, an argument could be made that the audience for this collection is unlikely to be searching for the work of a particular photographer, but that is a riskier assumption than that which informs leaving “Missouri River” out of a subject list. Considering this collection is dedicated to early railroad expansion, and bridges were an integral part of that expansion, it seems that the rivers over which the bridges were built should be access points for this particular collection.

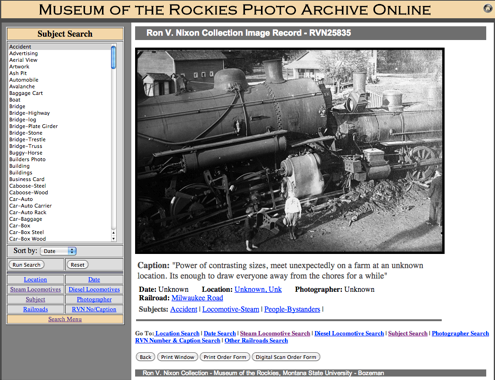

On the subject of subject headings, another item-level record is listed below.

The subject headings, “Accident”, “Locomotive-Steam” and “People-Bystanders”, are minimal at best. No mention is made of children, houses or barns, although the two children in front of the accident scene are integral to the nature of this photograph; it is more than just a photo of an accident.

Similarly to the Library of Virginia catalog, the caption seems to be where the fun is: “Enough to draw everyone away from the chores for a while.” I would imagine so.

These two catalogs are designed with different goals, different audiences and different levels of specificity. On a basic user level, the simpler descriptions and pre-defined search terms in the Museum of the Rockies catalog make it easier and more efficient to use. It was a simple matter to find my way back to images I had been referencing earlier; the catalog is memorable in that way. The Library of Virginia catalog represents a much larger, more diverse set of holdings, and the state library, in a state proud of its Southern heritage, presumably has more resources at its disposal than Montana State University. Extensive description and cataloging are necessary to make such a large collection accessible. However, while they may increase its accessibility to trained librarians and information professionals, much of this information is not particularly useful for a casual browser.

The Museum of the Rockies catalog is better designed from the point of view of knowing the audience. Information should be as complete as possible, but it is a reality of the times that creators of an online catalog, like any website, must know their audience and understand its needs. Despite its limitations, such as those discussed in the areas of subject headings and photographer listing, it is an easy catalog to browse, and its users are probably going to be more likely to browse than to attempt a targeted search.

The Library of Virginia catalog is better designed from an informational, description and searchability standpoint, but even that catalog and the professionals and resources it took to create it is not perfect. If one does not remember one’s exact search strategy, it is difficult to find the way back. Searches that seem like they should be effective for this prove to yield slightly different results, creating a frustrating experience.

One things these catalogs have in common, however, is that they exemplify the difficulty and contradictions of using text to describe a visual object.

No comments:

Post a Comment