Wet Day on the Boulevard, Paris by Alfred Stieglitz, 1894. George Eastman House

Invention

The carbon print was patented in 1864 by Sir Joseph Wilson Swan, an English scientist who had previously experimented with electrical engineering and had invented an early form of lightbulb. In his photographic experimentations, Swan built upon the ideas of Mongo Ponton, who, in 1832, “[demonstrated] the light-sensitivity of chromate salts” through the use of “potassium dichromate” (Arnow 137). Swan used this discovery to make a photographic plate using gelatin and pigment that was then sensitized with potassium dichromate. Swan later sold the patents of this process in multiple countries (to Autotype Printing and Publishing Company in England, Hansfstangl Company in Germany, and Dr. Robert Green in Fort Wayne, Indiana) and by “1868[,] commercial manufacturers produced carbon print tissue in more than fifty types and thirty colors, making the process applicable to commercial uses, including book illustration and fine art reproduction” (Arnow 139, Kennel 19). The carbon process was used particularly from the 1870s to the 1900s amongst pictorialist photographers (Kennel 19). Others later improved upon the carbon process. In 1878, Frederic Artigue “developed a carbon tissue that could be exposed to light and processed without intermediary transfer (direct carbon)” (Kennel 19). Later developments to the process were also made by Artigue’s son, Victor, and Theodore-Henri Fresson (Kennel 19). The carbon process also lended itself to the development of other processes, namely, the Carbro print (patented by Thomas Manly in 1905), which also employs the pigmented gelatin dichromate backing papers.

Cool Haven by Adolf Fassbender, 1933. Minneapolis Institute of the Arts.

The Process

The carbon process begins with Swan’s pigmented gelatin backing

paper, sensitized with potassium dichromate. It is then exposed to the negative with

light, “[hardening] the dichromated gelatin in direct proportion to the amount

of light it receives” (Kennel 19). After this exposure, the backing paper,

along with a new paper (on which the image will appear) are submerged in cold

water and pressed together. After a bath in warm water, the papers are pulled

apart and the excess gelatin is washed off. The following video demonstrates

the development process:

The end result of this process is hardened, laterally reversed

gelatin image. Correcting the lateral reversal requires transfer to an

intermediate backing paper, which is then sandwiched to the final paper (Kennel

19).

Identification

Carbon prints are noted for their exceptional tonal range,

including highlights and shadows, with highlights appearing “where the gelatin is thinnest” (Kennel 19). They are also relatively permanent, even when

exposed to light. Their namesake, carbon black, was the most common pigment

used in these prints. Other common colors included sepia and a bluish black. It

is the deep black color, however, “in combination with a slight relief when viewed under

magnification, [that] is the chief identifying characteristic” (Ritzenthaler

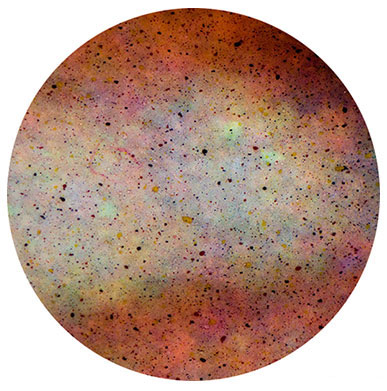

51). Also viewable under a microscope are bits of the pigment, as shown in this image from Graphics Atlas:

Additional

Resources:

Guide

to Modern Carbon Printing: http://www.carbonprinting.com/manual010810.pdf

Sir

Joseph Wilson Swan: http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/576273/Sir-Joseph-Wilson-Swan

A

Scientific approach to carbon transfers: http://www.alternativephotography.com/wp/processes/carbon-carbro/the-carbon-transfer-process

Works Cited:

Arnow, Jan. "The Carbon Print." Handbook of Alternative Photographic Processes. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1982. Print.

"Identification of Carbon Prints." Graphics Atlas. N.p., n.d. Web. 26 Feb. 2013.

Kennel, Sarah, Diane Waggoner, and Alice Carver-Kubik. In the Darkroom: An Illustrated Guide to Photographic Processes before the Digital Age. Washington D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 2010. Print.

Ritzenthaler, Mary Lynn., and Diane Vogt-O'Connor. Photographs: Archival Care and Management. Chicago: Society of American Archivists, 2006. Print.

No comments:

Post a Comment